Harrington, Hoff committed to clean commission race

In what is often a fierce partisan contest, this year’s candidates are unlikely to “go low.” Both Democrat and Republican are keeping things positive in the race that will determine county leadership.

Laramie Mayor Brian Harrington and local locksmith Thad Hoff are vying for an open seat on the Albany County Commission, each hoping to secure a four-year term as one of the county’s highest elected officers.

The commission race is countywide, meaning that all voters in Albany County, regardless of home address or party affiliation, will get to cast ballots in favor of either Harrington or Hoff on General Election Day, Nov. 5.

The result of this election will determine the partisan balance of the commission; the body could remain in Democratic hands with Harrington’s victory or shift to Republican stewardship with Hoff’s.

But both candidates have said they want to run on the merits, and have been promoting what they want to do in office while speaking very little about their opponent.

“I keep telling people: I’ve got a business I am going to go back to,” Hoff said. “Win, lose or otherwise, I still have to conduct myself like I’m a business owner and a responsible party. So the name-calling or any of that, that’s not going to happen.”

At the very least, Hoff said, the name-calling is not going to come from him.

“I’ve heard Brian called all sorts of things,” Hoff said. “‘He’s this’ or ‘He’s that’ — but it’s the same thing that they’re calling national candidates. I’m like, yeah, you guys have no idea what a socialist is. You have no idea what a communist is. There’s a civic duty. He’s doing it.”

For his part, Harrington is keeping his own campaign focused on the “civic duty” he’s performed as mayor — touting his work on housing reform and aquifer protection.

“I’m just going to tell folks the things I believe in and hope that’s enough to persuade them to vote for me,” Harrington said. “I’m running on the sort of things that I think are going to be best for the future of Albany County — and who my opponent is is maybe less important in that conversation.”

Harrington was more or less required to launch his campaign with that mindset. Throughout the Primary Election season, as Harrington sailed unopposed into his own party’s nomination, he could look across the aisle and see Hoff competing for the Republican nomination against three other GOP candidates.

Ultimately, Hoff clinched the nomination by a healthy margin. But in the fog of a hotly contested primary, that wasn’t clear. So Harrington had to be ready to run against the long-time city cop with a checkered past, the Rock River politico who’s in it for the conversations, or the mysterious other candidate who avoided media interviews and public forums.

In the end, Harrington wouldn’t be running against any of these challengers.

“It would have been helpful if there was some sort of obvious frontrunner, but every one of them, I think, stood a chance of winning,” Harrington said. “It’s sort of hard to mentally prepare for the race when you don’t know who’s on the other side.”

But now, the commission race has come into focus. Following the Primary Election, Harrington moved from “presumptive” to actual nominee and Hoff rose from that crowded Republican field to represent the other side of the aisle.

Hoff acknowledges that he and Harrington are offering county residents alternative visions for leadership — and he’d strongly prefer voters pick his own — but that doesn’t mean things need to get heated.

“If you want that same brand of experience and the same decisions [Harrington’s] made at the city, vote him in,” Hoff said. “You get the choice. You get to fill in the little dot. I’m not going to be absolutely heartbroken if I lose — but I’d like a seat at the table.”

Harrington and Hoff both attended a Progressive Voter Alliance meeting last week as well as a League of Women Voters forum three days later. They also completed the Laramie Reporter’s candidate questionnaire, and their full answers to that questionnaire will be published tomorrow.

Democrat, Republican, Commissioner

The partisan lean of the Albany County Commission, a three-member body, is often determined by the election of a single seat.

This happened in 2020 and it will happen again this year.

Whoever wins the open county commission seat in November will join one Democrat (Pete Gosar) and one Republican (Terri Jones), meaning the partisan majority of the commission for the next two years will reflect the party affiliation of this year’s General Election victor.

“I don’t think that’s going to have any bearing at all,” Hoff said. “I don’t envision getting a phone call from somebody who’s a Republican saying, ‘Hey, this is the way it’s going to be,’ or having Terri Jones sit me down and tell me how it’s going to be — any more than if Pete calls and says, ‘Hey, this is going to happen.’”

Rather than toe any party line, Hoff said he’s looking forward to making decisions alongside two other individuals.

“I think hearty debate in this community is going to be helpful,” Hoff said. “I can talk to Pete, I can talk to Terri. They’re two different wavelengths, though. They have absolutely different opinions. And I think if you have three dissimilar folks, then there’s actually a decent interaction as to how things are going to be handled … You actually have to convince [them] and it’s got to be for the greater good of the community.”

Hoff said “90% of the time,” the various approvals and other small items the commission works through on a bimonthly basis don’t touch partisan politics. He said voters can expect the broad agreement that exists on those small items to persist, whether he’s on the commission or his opponent is.

“I don’t really care about national politics, even in the slightest,” Hoff said. “I don’t know that it has a lot of bearing on the local community. It does [with] state land leases or federal leasing and coal mining and renewable energy and non-renewable energy — but that’s a lot of state politics. That’s not necessarily Albany County.”

Harrington also views the vast majority of the commission’s work as essentially and reliably non-partisan. But as the years-long debate about aquifer protection demonstrated, partisanship is occasionally a useful lens for understanding local political divides.

Aquifer protection and partisan politics

The Casper Aquifer is the source of a majority of Laramie’s drinking water. In recent years, advocates have sought to protect that underground water source from contamination by restricting what can be built on the land above. These advocates were typically Democrats.

There was pushback to these proposals from those who didn’t want to restrict — or wanted less stringent restrictions on — what could be built on the land above the aquifer. This pushback typically came from Republicans.

The battle between the two sides played out in lawsuits, elections and commission meetings. Ultimately, the aquifer protection advocates prevailed, but they only achieved their main goal — a unified city-county Casper Aquifer Protection Plan and specific zoning regulations for the overlay zone — once Democrats had taken the commission.

Among commissioners, the aquifer debate reliably fell along party lines.

In a particularly memorable and heated commission meeting, Republican Commissioner Heber Richardson — frustrated and outnumbered — stormed out of the room, using colorful language to describe how his time could be better spent.

Harrington is hoping the Democratic-Republican divide on aquifer protection is either softening, or else that it was always a mirage.

“My hope has always been that what has felt like a partisan divide on the commission is maybe more of a geographic divide, or that something else might explain it,” he said. “Because I don’t understand how partisanship paints the difference between whether you want clean water or not … There are plenty of Republicans that care about your drinking water too.”

Hoff is not planning to roll back aquifer protections. But he has not made upholding and defending those protections a central pillar of his campaign, as Harrington has.

On other issues, what could be seen as a partisan divide has been less consequential.

For example, when the commission approved the much-debated Rail Tie Wind Project in 2021, it did so with a unanimous vote — but Commissioners Gosar, Ibarra and Richardson gave very different reasons for their ‘aye’ vote. While Ibarra cited the need to take action on climate change, Richardson argued the county had no right to block a private company that had dotted its i’s and crossed its t’s.

Those statements reflect a recurring division between liberals and conservatives — liberals being more willing to use the government for what they view as the common good and conservatives being less willing to mess with the rights and privileges of free enterprise. But those generalizations don’t describe every politician and the liberal-conservative divide can be more or less pronounced, given the year and the issues on the table.

That division appears less pronounced this year — at least when it comes to the commission race between Harrington and Hoff.

Harrington, the Democrat, has touted his work to deregulate housing development, removing barriers that were interfering with the free market. Hoff, the Republican, talks about balance; he said he and his supporters don’t want to see heavy-handed government, but also that there are trade-offs and he intends to approach problems by weighing all sides.

During the League of Women Voters forum last week, Harrington and Hoff disagreed about a few topics, but few that would fall within the purview of the county commission.

Harrington was more hesitant than Hoff about recent efforts to fund public schools with private dollars, and Hoff was more hesitant than Harrington about the state granting counties “home rule” — the brand of local control enjoyed by cities.

But these are more pressing issues for the candidates running in Senate District 10, who were sharing the forum stage with Harrington and Hoff and to whom the questions were primarily directed.

Experience and preparedness

The most obvious difference between the candidates is in their respective experience. While Hoff has never before held an elected position, Harrington has served as a Laramie City Councilor for six years and as the city’s mayor since early 2023.

During his tenure, Harrington has voted for police accountability measures, zoning reforms that encourage affordable housing, protections for rental tenants and the approval of the Casper Aquifer Protection Plan. But perhaps his proudest achievement is the city’s purchase of the Bath Ranch — a significant tract of land with even more significant water rights.

“Long term, nobody will know my name, nobody will know any of the councilors’ names,” Harrington said. “But some councilor in 40 or 50 years is going to think back and go, ‘Those guys had a good idea.’”

They’ll say it was a “good idea,” Harrington said, because the purchase has greatly expanded the city’s water portfolio and has ensured the city’s access to drinkable water long into the future — at a time when communities across the west are worried about their own future access.

“I hope my kids stay in Laramie when they’re older, because I know that they'll have drinking water in Laramie and you can’t say the same if they move to Phoenix,” Harrington said. “But I know here they’re going to have clean water, and that helps me sleep at night.”

In the last four years — during which Democrats have held the county commission and a majority of liberals and moderates have run the city council — the governments have started collaborating more closely. This was especially true during the push for aquifer protection, which resulted in a unified city-county plan for the first time.

If elected to the commission, Harrington hopes to maintain this relationship from the other side.

“When I mulled over the things that I had really truly enjoyed working on — they all felt like they could continue quite smoothly at the county,” he told the Reporter shortly after his initial campaign announcement. “This general partnership between the city and the county that’s developed over the last three years, I think, has really been really beneficial to the taxpayers.”

But Hoff is skeptical about how much Harrington’s experience as a councilor will serve him as a commissioner.

“I don’t know that the county’s ready for the city brand of government,” Hoff said. “There’s a lot more cooperative efforts that have to happen at the county just to make everything work, because the budgets aren’t huge. The city can create their own rules and regulations. The counties govern more by state statute.”

The commission also has to get by with just three electeds — a third of the city council’s nine.

“You make a bad decision at the city, there’s probably somebody who’s going to catch it,” Hoff said. “You make a bad decision at the county, and it could affect somebody's livelihood — stockgrowers, water, land use.”

But Harrington said there’s a practical knowledge about getting things done that he’ll bring with him if elected to the new role.

“The job of commissioner is one that I’m ready to do from the first day in office,” he said. “It won’t feel foreign to me to speak in Robert’s Rules, or to understand how to read the agendas, or who’s responsible for what piece.”

Keeping up with the commissioners

Apart from procedure, both candidates say they keep up with the business of commission in their own ways. Neither regularly attends commission meetings.

Harrington said he doesn’t need to, given his unique position as a city councilor. The council meets regularly with the commission and Harrington talks frequently with Ibarra, the Democratic commissioner who has endorsed Harrington as her replacement.

“I talk with the commissioners, a couple of them,” Harrington said. “We talk all the time. In particular, Sue and I are quite close. I’ve been really proud of this back and forth that we’ve had going on for the last three and a half years or so. We’ve been able to work together on stuff, and that takes constant communication.”

Harrington said this keeps him appraised of what the commissioners are dealing with.

“I’m not going to watch them sign a bunch of vouchers or something like that,” he said. “But I keep up with what they’re up to.”

Hoff takes a similar view. He said commission meetings are “pretty boring” — consisting mainly of minor approvals and sign-offs — and don’t tell observers much about what the county government is actually up to.

Like Harrington, Hoff gets a lot of his information about the business of the county through interpersonal conversations.

“My butt being in a seat doesn’t make me a better candidate for county commissioner; it makes me a better audience member,” Hoff said. “It’s like me going to a movie theater and going, ‘Oh, I just watched a dozen Spielberg movies, I’m a director.’ It has no bearing on the proceedings. Talking, and understanding the thought process, and talking in the wings outside the meeting — that’s when you really get the: ‘Well, why are you thinking this way?’”

Hoff said sometimes it’s appropriate to get the “40,000-foot view,” but most of the time you’ll gain a deeper understanding of an issue from “knowing who to ask, or what question to ask” of the folks on the ground.

“If [Harrington] is reading a report that city hall prepared for him, I don’t know that they’re getting the same information as physically talking to the supervisor or the guy who is turning the wrench,” he said. “It’s a different knowledge base.”

Fundraising philosophies

Commissioners serve staggered four year terms. During midterm elections (those without a presidential race), two commission seats are on the ballot. During presidential election years, such as this one, the other commission seat is up for grabs.

Whether Albany County voters are deciding a majority or a minority of the commission, the countywide race often inspires fierce competition.

In 2020, Democrat Sue Ibarra unseated Republican Terri Jones, flipping the commission from red to blue in an election decided by just 57 votes.

In 2022, Jones regained her seat, replacing fellow Republican Heber Richardson, while Commission Chair Pete Gosar, a Democrat, kept his own. The Democratic majority was maintained.

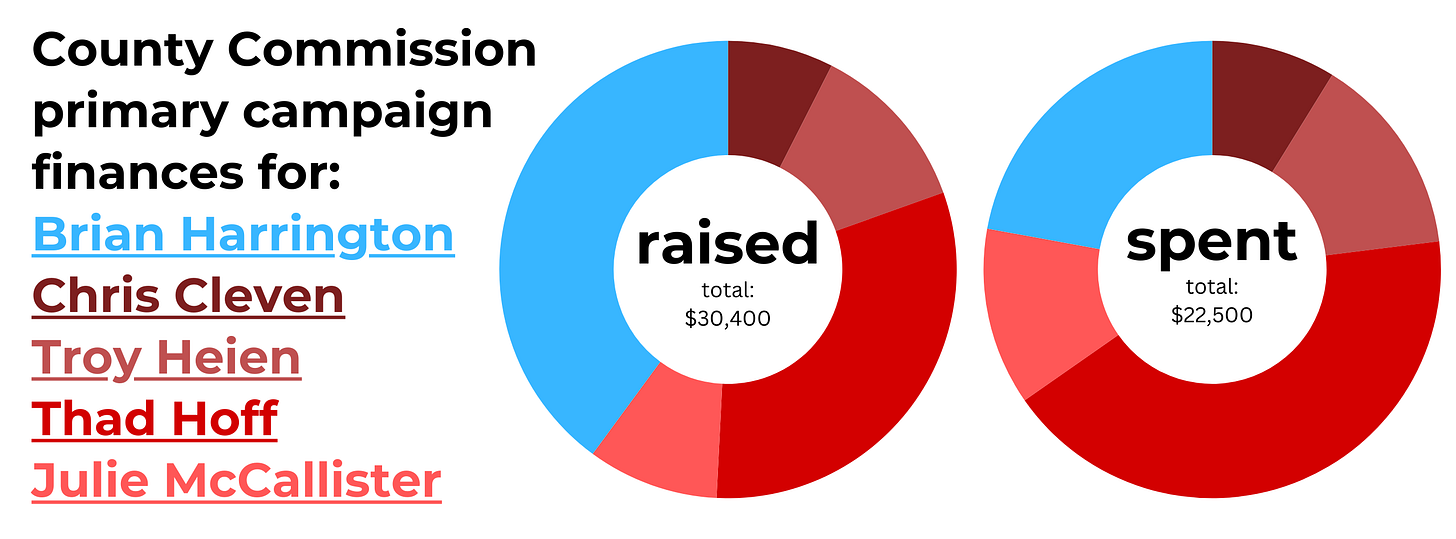

In both elections, candidates spent big. Ibarra and Jones raised a combined $46,000 in 2020 (spending more than $35,000 of that) while Jones, Gosar and the other 2022 candidates raised $41,000 (and spent $31,000) two years later.

So far, Harrington and Hoff have raised a combined total of more than $21,500 in the primary alone. But they are funding their respective campaigns in very different ways.

Hoff is — as of his latest campaign finance filings — entirely self-funded.

“I did have some offers for campaign funding,” he said. “Some of them were from customers. Some of them were from friends. I knew the names would be published, or at least records requests would reflect it, and so I chose to fund it myself and keep their names off — at least for now.”

Instead, Hoff put up about $9,500 of his own cash to pay for campaign signs, newspaper ads, radio spots and other promotional material.

“I’m fortunate enough my business did well this year, and I had some money saved up for either funding other campaigns or my own,” he said. “I really don’t want to be beholden to anybody or their ideals. If it’s offered without strings, that’s fine. If it’s a community member that’s concerned about something in the community, fine — but no, I don’t need special interest.”

Harrington takes a different view of political donations. He sees them as vital statements of support.

“I’m really trying to run this campaign by and for my neighbors, and I think my campaign finance reports show that to be true,” the mayor said. “I’ve always felt like how you pay for your campaign is indicative of the support you have, and having as many donors as I have — and in varying degrees, like the level of gift — that’s got to mean something. I’m certainly proud of it.”

All told, Harrington had raised more than $12,000 ahead of the Primary Election — nearly $10,000 of which came from individual donors giving between $10-$1,000 a piece.

As of his latest campaign finance report — filed in August — Harrington had spent about $5,000, retaining the bulk of his funds for the general.

“I don’t know if it’s enough, and I don’t want to lose because I didn’t raise enough money,” he said. “So I’m going to continue to raise money throughout the entirety of the race.”

Hoff didn’t say whether he would start accepting individual donations, or even donations from PACs and the local GOP party. But he’s aware that the race for commission can often be decided by a razor-thin margin.

“I did spend probably way more money than I had to,” Hoff said. “I didn’t want to lose by 32 votes.”

Both Harrington and Hoff completed the Laramie Reporter’s candidate questionnaire. That questionnaire, with answers from both candidates, will be published tomorrow.