Albany County ranchers push for rural school

Undeterred by a recent loss at the Wyoming Supreme Court, the Andersons hope the state will fund a one-room schoolhouse for their two children in extremely rural Garrett, Wyoming.

A line item in the state budget could give one Albany County family something they were denied by the Wyoming Supreme Court: a rural school for their children.

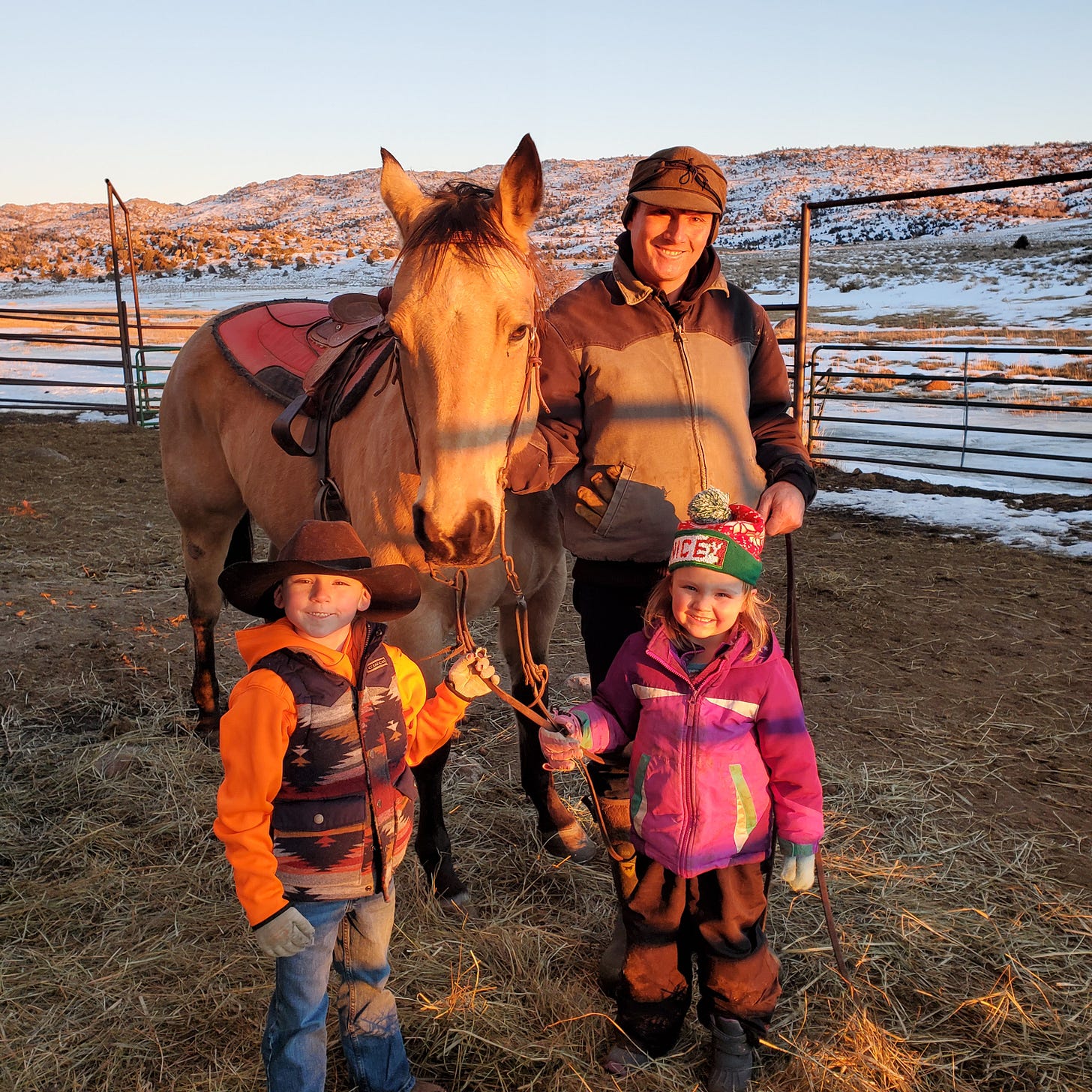

Carson and Anna Anderson work the Slow and Easy Ranch in Garrett, Wyoming in northern Albany County. For two years, they’ve been fighting to establish a rural school for their children Emmitt, 7, and Waverly, 4.

The family has been frustrated at nearly every turn. What started as an arduous bureaucratic process eventually graduated to a lawsuit and an appeal to the state supreme court. Now, the issue is at the heart of a budget amendment that may or may not survive the 2024 Budget Session of the Wyoming Legislature.

But for Anna Anderson, the issue is simple: Her family needs a schoolhouse and the suggested alternatives don’t cut it.

“I’ve really poured my whole heart into this for the last two years,” she said. “When you’re a mom, you do whatever you can. And this has been a special hell on my family.”

In good weather, the Andersons’ ranch is an hour or more from the closest town, Rock River. In bad weather, the family is completely isolated. During the winter months, it’s not uncommon for the Andersons to find themselves snowed in for weeks at a time. Even when they’re not literally snowed in, winter travel remains a dangerous chore.

“The roads are just not very forgiving — it doesn't take much to overcorrect and just flip,” Anna said. “Having a dirt gravel road just makes everything slower. You just can't go 60 miles an hour — you go 30 to 40. It’s very open and no one’s going to help you change your tire when you get a flat tire. You’re going to have to just figure it out or wait a couple hours if you have car trouble.“

In the long battle to establish a rural schoolhouse for their children, the Andersons have just faced a mighty setback: the Wyoming Supreme Court rejected a lawsuit the family brought trying to compel the state to kickstart the school.

But all is not lost for the Andersons. Their delegate in the State House of Representatives, Rep. Trey Sherwood (HD-14), pushed for an amendment in this year’s budget bill that would bankroll the construction of a rural schoolhouse in Garrett, Wyoming.

The Andersons are hoping that amendment survives the session. Anna said it’s a matter of “fundamental fairness” for her children, but it’s also important for the future of ranching in Albany County.

“I chose this life knowing that there would be rural schools, knowing that was the precedent and that was just the norm,” Anna said. “What we do as ranchers is our legacy. It goes from generation to generation, and that’s the way it is and that’s the way it’s always going to be in our family.”

If the Andersons do not get the school they’re pushing for, the family will have to split up for long periods of time, one parent living in town so the children are close to their school, the other back home, managing the herd.

Schroeder rejects Buckle School, offering virtual school as alternative

Since 2019, the Andersons have been looking to establish a rural schoolhouse under the jurisdiction of Albany County School District No. 1. In early 2022, they got the news they were waiting for: The Albany County School Board had approved the formation of the “Buckle School,” agreeing to construct the actual schoolhouse and pay for the live-in elementary teacher.

“It was a big relief, because it was such a process to get it that far,” Anna said. “It was during calving season. I'll never forget it. I help my husband with the night shift and I just remember we had a pretty busy night with the heifers and I was exhausted. I had had a couple hours of sleep. And when they said it’s a done deal, it was just such a relief. I was just like, ‘Finally!’ and you know, it came at a perfect time.”

Rural schools are not a new concept in Wyoming or in Albany County. In fact, a majority of schools in the state are classified as rural, and the existence of rural schools is a point of pride for many in Wyoming.

But establishing such a school requires securing multiple levels of approval. In this instance, the Buckle School was approved by the local school board. It was then vetted by the State Construction Department, which also signed off on the proposal.

But then that proposal landed on the desk of then-Superintendent of Public Instruction Brian Schroeder. As the later Supreme Court ruling recounted:

(T)he Superintendent found he could not grant the application because the County could provide adequate education without creating a new school and the cost effectiveness of the proposed reconfiguration weighed overwhelmingly against approval given the advancement of virtual education options. The Superintendent also acknowledged creating a new rural school would be consistent with past practices in Wyoming, but he concluded it would now be inconsistent with the values of fiscal responsibility, cost effectiveness, and fiscal integrity.

Schroeder’s rejection stopped the project in its tracks. But a month later, the Andersons made their case again, this time in a lawsuit, taking aim at the school district, the state Department of Education and the Superintendent of Public Instruction.

Wyoming Supreme Court rules state can’t be forced to build rural school

Specifically, the Andersons asked Albany County District Court to issue a writ of mandamus — a court order compelling lower government officials to perform one of their specified duties.

In this case, the Andersons argued that state law — specifically Wyoming State Statute 21-13-309(m)(vi)(A) — required education officials at the county and state level to approve the Buckle School.

That section of law states that approval of such schools:

… shall be based upon the appropriate delivery of the required educational program, the cost effectiveness of the proposed grade reconfiguration for delivery of adequate educational services to students with block grant resources, district wide capacity of school educational facilities … and any extraordinary circumstances related to the safe and efficient delivery of the education program to students[.]

The District Court rejected this and other arguments for mandating approval of the Buckle School. So the Andersons appealed the district court’s decision to the Wyoming Supreme Court.

The supreme court ultimately upheld the lower court’s ruling.

In a decision penned by Justice Lynne Boomgaarden, the court argues that it cannot issue a writ of mandamus in cases where the government officials in question have discretion to make their own judgment calls. Boomgaarden referred back to an earlier supreme court case:

“We have stated: The function of mandamus is to command performance of a ministerial duty which is plainly defined and required by law. Mandamus will not lie unless the duty is absolute, clear, and indisputable.”

The supreme court found a similar fault with another argument advanced by the Andersons. The family also alleged their right to a rural school under a separate chapter of law — Wyoming State Statute 21-4-401.

That chapter requires school districts to “provide transportation or maintenance for isolated elementary, middle, junior high or high school pupils resident within the district, whenever it would be in the best interests of the affected children to provide transportation or maintenance than to establish a school to serve these pupils.”

According to the ruling, this does not grant the Andersons an enforceable right to the creation of a rural school. Instead:

“It allows parents or legal guardians to request transportation or maintenance payments from the school district and expressly permits them to enforce their rights under the statute through writs of mandamus,” Boomgaarden writes. “But it does not afford Petitioners any right to their own rural school or permit a writ of mandamus requiring the school district or State of Wyoming to build one.”

In essence, the state superintendent is allowed to decide that transportation reimbursements or virtual learning programs are sufficient alternatives to building a one-room schoolhouse.

When Anna Anderson learned of the supreme court ruling, she was willing to accept its legal interpretation. But she said neither of those options would work for her children.

Transportation, however it’s paid for or provided, is difficult and sometimes impossible in the winter months. And she believes virtual education is not as effective or as stimulating as education that comes with a more personal connection.

“All I know is this is a fundamental fairness issue, and all children in Wyoming are guaranteed an education,” Anna said. “And this has been done recently for people similarly situated as us, and our kids are being treated differently.”

As the situation stands, Emmitt and Waverly are working through a Christian homeschooling curriculum. Anna doesn’t view this as a long-term solution.

“I get that parents are the number one educator for kids,” she said. “It’s just I have a lot of responsibilities — help them to be good humans, and help them with life skills and baking and all that. I’m not a math teacher or a science teacher. So trying to navigate that — it’s been really hard.”

Despite their losses in the district and state courts, the Andersons’ luck has not run out just yet.

Sherwood adds Buckle School funding to state budget bill

Wyoming lawmakers will gather in Cheyenne this month to hammer out the state’s budget.

The “budget bill” those lawmakers will be discussing, debating, and altering is the product of months of work involving interested members of the public, individual state agencies, Gov. Mark Gordon and — perhaps most significantly — the Joint Appropriations Committee.

Rep. Trey Sherwood (HD-14) — who represents most Albany County residents north of Laramie, including the Andersons — serves on that committee. She therefore got an earlier crack at the budget than most lawmakers.

Sherwood used that opportunity to push for an amendment that could address the Andersons’ woes. Her amendment socks away up to $300,000 from the state general fund to establish a schoolhouse in Garrett.

“This is one step to move towards a solution for our hardworking rural ranch families in the state and to uphold an existing precedent,” Sherwood said.

Anna and Carson Anderson appeared before the appropriations committee last month, speaking in favor of the amendment and proposing more sustainable solutions.

“We want the legislators to help protect rural children and their education in Wyoming,” Carson told the committee. “There could be an opportunity to look into having mobile homes or buildings to be used as classrooms and housing for the teacher. This is how it was done in the past and after one school was used, it was moved to the next family … Rural community children are equal to in-town children. Both need a safe and local education.”

Ultimately, the committee endorsed the amendment — which means the $300,000 line item is now a part of the budget bill going before the legislature next week. Lawmakers could bring a motion to reduce or remove that funding, but if they take no action, the line item will remain.

If school funding passes, it’s all up to Degenfelder

Even then, the Buckle School will not be a done deal. The amendment simply makes the funding available. The proposal will have to go through the bureaucratic approval process once more. It will need to secure the support of the school board and the State Construction Department again and, for the first time, win the support of the State Superintendent.

Schroeder, who rejected the Buckle School in its first iteration, is no longer the state’s chief of schools. He has been replaced by Megan Degenfelder, who was elected in 2022.

Ultimately, Degenfelder will have the final say on the hoped-for schoolhouse.

“She still has the statutory authority through rulemaking to say yes or no,” Sherwood said. “That’s where the process stopped last time, when Brian Schroeder said no. So this line item in the budget does not supersede that process. That process still has to occur.”

If the school is not approved, the $300,000 set aside for its construction will revert back to the state’s general fund.

So it’s a long road still, and there are plenty of points along that road that might prove fatal. But Anna Anderson is trying to stay hopeful.

“This is our only hope right now,” she said. “This is our only chance.”