Free speech or harassment? Breaking down the union preacher’s lawsuit against UW

The First Amendment stops the government from “abridging the freedom of speech.” But UW argues Schmidt’s banner was harassment, not speech, and that his history shows a pattern of misbehavior.

For more than a decade, the “Bible Guy” has been a regular feature on campus, known for taking up a regular post in the student union and evangelizing to passersby, promoting a worldview grounded in biblical literalism and opposed to the scientific consensus on issues as varied as vaccines and dinosaurs.

But that preacher, Todd Schmidt, was absent through the spring 2023 semester, and has now brought a federal lawsuit against the university, claiming it violated his constitutional rights to free speech, due process and equal protection.

Schmidt was temporarily suspended from tabling in the union eight months ago, when he displayed a banner taking aim at transgender people. The sign insisted that sex is binary (which is false) and highlighted a specific transgender student by name.

The incident came amid a backdrop of rising anti-LGBTQ sentiment. Schmidt’s banner was the third anti-LGBTQ incident on the UW campus that week, and recent anti-transgender violence in Colorado had set UW’s queer community on edge. Nationally, the queer community — especially youth — are living in a “state of emergency” as state legislatures introduce and pass laws designed to restrict transgender freedoms and limit queer people’s participation and visibility in public life.

Where those laws are aimed at limiting acceptance in educational settings, queer children feel less safe, are actually less safe, and are less likely to succeed academically. It also remains true that respecting a child’s chosen name or pronouns reduces depression and suicidality.

These realities underpin the university’s response, its decision to ban Schmidt and its subsequent defense of that decision in federal court. UW implores the court to:

Imagine the Wyoming Union breezeway lined with tables, with each table manned by a person or entity singling out an individual University student. Imagine that at each such table, the targeted student is harassed solely based upon membership in a protected class — one for her gender, one based on his race, one based on her color, one based on his national origin, one based on a disability, one based on a religion, one based on their sexual orientation, one based on her gender identity. According to Plaintiff, all of that conduct would be protected free speech, and the University would be required to allow it to happen.

Schmidt’s lawsuit raises questions about free speech on college campuses, what visitors to campus can say or where they can say it, the line between free speech and harassment that takes the form of speech, and the proper role of universities in stamping out discrimination and harassment.

In truly bad journalistic form, this story will not answer the question posed in its headline. Rather, the aim is to lay out the argument on both sides and provide an update on where the case currently stands.

The ballad of Todd Schmidt, anti-LGBTQ preacher

Laramie Faith Community Church Elder Todd Schmidt started tabling in the Wyoming Union nearly two decades ago.

For many years now, he has reserved a spot every Friday, hoping to share his worldview with students as they pass through the union and the campus’ main thoroughfare.

It’s a good place for it. Between classes, the thoroughfare is probably the most densely populated area in the state.

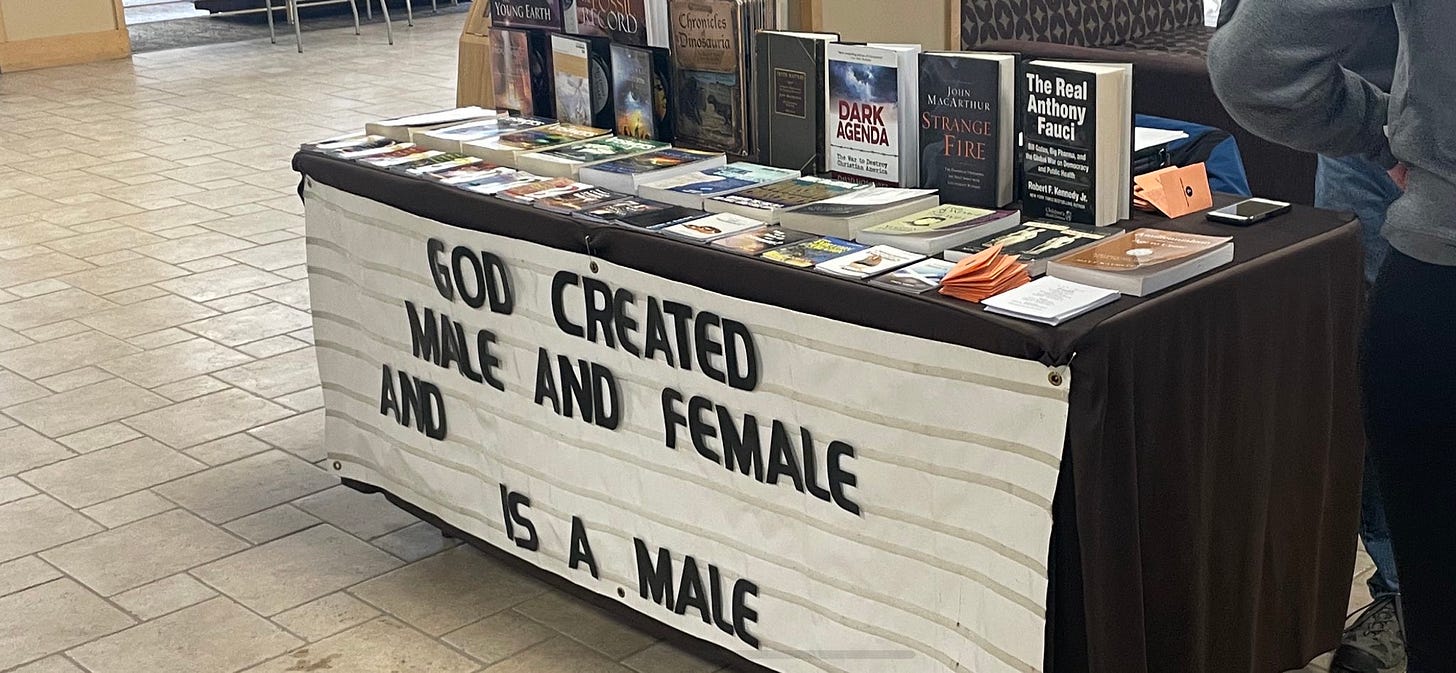

Schmidt’s table was often covered with DVDs and books on a wide range of subjects — from vaccine conspiracism to young earth creationism — and the front of his table usually bore a velcro banner with a message of the day spelled out in plastic lettering. Schmidt describes these messages as “thought-provoking.” Some example included:

“Are you bad enough to go to hell?”

“Atheists don’t exist. Change my mind.”

“Evolution is fake news. God is true and is creator.”

“Confused about your gender? I can help.”

On the morning of December 2, 2022, after “thinking and praying about it,” Schmidt lettered a new message on his banner.

Citing information gleaned from a right-wing podcast about students at the University of Wyoming, Schmidt spelled out:

“God created male and female and Artemis Langford is a male.”

Langford is a transgender woman enrolled at UW and inducted into the school’s Kappa Kappa Gamma chapter.

A feature in the student newspaper had celebrated her historic induction into the sorority, and right-wing commentators across the country had latched onto her specific inclusion as a symbol of a world gone astray.

The attention has radically altered Langford’s life. Media pundits such as Megyn Kelly and Laura Ingraham have mocked her on national television. Threats have been frequent. Her character, her appearance and her alleged failure to conform with feminine standards have been policed by the likes of Kelly and Ingraham, but also in a separate lawsuit seeking to ban her and every other transgender woman from Kappa sororities nationwide.

Schmidt has asserted, in court filings, that "his intended message was not designed to target Artemis Langford personally or offend anyone, including Langford."

Students, including some members of Langford’s sorority, defended her in the student union in December. They debated Schmidt and blocked his transphobic message with their bodies.

Eventually the commotion drew the attention of UW officials and Dean of Students Ryan O’Neil told Schmidt to remove Langford’s name from his sign. After some argument, he did, and stayed in the union for the remainder of the day, with a sign that read “God created male and female and [blank] is male.”

The incident ignited the UW community. Several students, faculty and alumni asked on social media, in letters to the school and during public silent protests why UW allowed Schmidt to stay for the rest of the day.

Surely, they argued, taking aim at a specific student is enough to warrant suspension from campus. Others argued the distinction between his naming of a specific student and his more general anti-trans message was nonsensical — certainly, they said, rejecting the validity of all trans people is just as discriminatory as rejecting the validity of one.

Following this uproar and an administrative review of university policy, Schmidt was banned from tabling in the union for one year. The ban applies only to tabling. Schmidt is still allowed to physically enter the union and to proselytize anywhere else on campus.

But he is prohibited, for now, from reserving and staffing a table in the Wyoming Union.

This, however, is intolerable to Schmidt, who has now filed a federal lawsuit asking for the elimination of some language from university policy, a declaratory judgment that his rights were violated, and monetary damages.

Schmidt: My banner was not “discriminatory” and I was banned for my opinions

Schmidt argues across various court filings that the case is straightforward.

“UW Officials determined Schmidt’s view on Langford’s sex is not orthodox and censored it for this reason,” his lawsuit alleges. “They committed viewpoint discrimination with the censorship.”

In essence, Schmidt argues that his tabling privileges were revoked because of his opinions, not because he shared them improperly or inappropriately.

Although his sign specifically and prominently named an individual student, Schmidt claims he did not “target” that student.

"His intended message was not designed to target Artemis Langford personally or offend anyone, including Langford,” the lawsuit states.

Therefore, Schmidt argues, his actions do not constitute “discriminatory harassment.”

“UW Officials rely on an overly broad interpretation of ‘discriminatory harassment’ for its table ban, which application engulfs too much protected speech within the proscription,” he states in a subsequent motion. “The message did not create a hostile environment, affect Langford’s academic standing, educational benefits, or create any harm to Langford in any meaningful way. Langford did not suffer … any harm from Schmidt’s sign.”

So Schmidt is asking for a preliminary injunction — which would allow him to return to the union immediately. He’s also seeking some more permanent victories. He lists five causes of action in his original complaint. He alleges that UW:

Violated the free speech clause of the First Amendment by censoring him;

Violated the free speech clause of the First Amendment by banning him from tabling;

Violated the due process clause of the 14th Amendment because specific paragraphs in university policy “lack objective standards”;

Violated the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment by banning only Schmidt and not other tables with different views;

Violated his right to be free from unconstitutional conditions generally.

Specifically, Schmidt takes aim at two paragraphs from UW’s student union policy.

Section 2.B.4: “(Tabling) requests may be denied for reasons which include, but may not be limited to, conflict with the mission of the University, conflict with the mission of the Wyoming Union, unfeasible setup/turnaround time, and historic negligence or abuse.”

Section 5.B.15: “ … Language or actions that discriminate or harass the above groups will not be tolerated. Students are expected to recognize that respecting the dignity of every person is essential for creating and sustaining a flourishing University community. Students should act to discourage and challenge those whose actions may be harmful to and/or diminish the worth of others, in accordance with the Student Code of Conduct.”

Schmidt argues the university cannot enforce its mission through the acceptance or rejection of tabling requests, and that it cannot enforce the anti-discriminatory language in the second paragraph.

UW: Schmidt has a history of misconduct and his anti-trans speech constitutes discriminatory action

Not so fast, argues the university.

Responding in court filings of its own, UW argues it has a right — and even a legal obligation — to prevent and punish discrimination and harassment, even if that discrimination or harassment comes in the form of words. Accordingly, it states its ban was “appropriate and lawful.”

“Plaintiff’s actions constituted discrimination and harassment of the student,” UW alleges. “They were not protected speech.”

Some speech can be banned if it falls into a broader category of prohibited actions and just happens to take the form of spoken or written words, UW argues. For example, inciting a riot would be illegal not because the speaker holds a criminal opinion, but because they are engaging in a criminal action.

“Whatever viewpoint the discrimination and harassment represented or arose from was irrelevant, as the University was not targeting any expressive content of Plaintiff’s speech,” UW alleges.

Schmidt argued in his own filing that he would not have been punished for a banner stating, “Artemis Langford is a female,” but the context of Schmidt’s statement has to be viewed in the wider legal and cultural context, UW argues.

“Plaintiff’s conduct, which he essentially characterizes as harmless with respect to the student he targeted, cannot be viewed in a vacuum,” UW alleges. “In 2023, using a student-centered educational facility to repeatedly target a transgender female student — and doing so solely based on her membership in a protected class — is discrimination and harassment.”

Further, there are federal laws meant to counter discrimination and harassment, such as Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and Title IX of the 1972 Education Amendments. There have also been more recent legal developments when it comes to the rights of trans people to be free from discrimination, including a 2020 Supreme Court ruling finding that sexual orientation and gender identity are protected classes. Even the concept of intentionally misgendering students has started to be worked out in the courts.

“Not surprisingly, Plaintiff's Motion pays little attention to this issue,” UW argues. “That is likely because confronting the issue would require Plaintiff to concede that the legal landscape has changed drastically over the last decade, especially related to the protected class status of the LGBTQI+ population.”

UW alleges that even before the December incident, Schmidt frequently violated union tabling policy by “leaving his table and confronting students.”

“On numerous occasions, Dean O'Neil was required to warn Plaintiff that he needed to comply with the University's policies and procedures related to using tables,” UW alleges.

According to UW, Schmidt’s behavior only got worse:

By 2021, issues with Plaintiff’s non-compliance with the Union Policies and Procedures had risen to the level that the University decided it needed to start documenting complaints about Plaintiff. As a result of those complaints, University employees verbally warned Plaintiff to stay behind his breezeway table and act in a non-confrontational manner toward passersby. Plaintiff’s non-compliance nonetheless continued. For instance, on April 18, 2022, a student complained to the University that Plaintiff "got in people's faces" while trying to talk to them. On April 30, 2022, a student complained that Plaintiff ran after him when he refused to talk to him. On November 11, 2022, a student staff member complained that Plaintiff approached him (i.e., left his table) to confront him about his shirt. Various individuals have complained about how Plaintiff treats female members of the University community. One staff member reported Plaintiff telling her that he does not respect female authority.

This alleged pattern of behavior informed the university’s ban and is also part of the reason UW asked the court to not grant a preliminary injunction.

“If history is any indicator, Plaintiff’s presence would be disruptive and cause safety concerns for students and employees,” UW alleges. “There is a strong public interest in students and employees knowing that the University will protect them from unwelcome conduct, including harassment. There are also strong public interests in the University being able to maintain order on its campus and sanction individuals who violate its policies and procedures.”

So where does the case stand and what’s next?

This lawsuit is still in its early stages. Schmidt filed his original complaint June 15, just one and a half months ago. UW responded with its answer on July 24, denying every major allegation Schmidt made about his constitutional rights.

Simultaneously, Schmidt sought a preliminary injunction — an immediate form of relief that would let him return to campus while the court decided the case. Schmidt asked for this injunction on June 28, and UW responded to that motion, asking the court to deny Schmidt’s request, on July 24, alongside their answer to the main complaint. Schmidt asked once more, on July 31, for the court to grant his preliminary injunction, but the court has yet to weigh in.

The court has also yet to weigh in on the original, overarching complaint. Both sides are hoping the court will rule in their favor with a declaratory judgment — meaning there would be no trial.

Notably, the ban is only in place for a few more months. Whatever happens in the case, Schmidt will be allowed to table in the union again starting January 2024. UW has not taken aim at Schmidt’s wider, more general anti-trans message — meaning that when he returns, he’ll be able to share similar messages on his banner.

This lawsuit will only determine whether he and other tablers have a right to name specific, individual students, as Schmidt did with Artemis Langford.

Langford is now awaiting the results of two, separate federal lawsuits — Schmidt’s free speech lawsuit here and the unrelated lawsuit seeking her removal from the sorority. Neither lawsuit asks for relief from Langford herself, but both spend significant time discussing her position on campus and criticizing her appearance.

This lawsuit should've been dismissed upon submission. Absolutely wild that this guy will do anything to ensure he can continue harassing college students.

Maybe a street corner would be better for his Hate and Harassment Speach.