Looking Back: ‘The Artful Dodger’

One year ago, this exposé highlighted a Laramie landlord notorious for the state of his rentals, who kept more than $16,000 by allegedly double-charging tenants and avoiding court.

Max Bossarei’s business practices as a landlord were brought to light in the following feature one year ago.

In the months since, Bossarei has been successfully served at least twice by a private process server and was ordered to pay Brad and Kimberly Beck roughly $4,200 for the unreturned furniture mentioned in the story below.

Jessica Stalder was more directly tied to Bossarei’s business in two subsequent stories. She resigned from the Laramie City Council in July, citing the demands of her position as Hospice of Laramie executive director.

Earlier this month, the city council passed rental regulations on a 7-2 vote. When they take effect next year, rental units will have to be weatherproofed, structurally sound and free of pests or mold. Major plumbing, heating and electrical work will have to be performed by licensed professionals, and appliances furnished by the landlord will have to be maintained.

The regulations also require landlords to register each unit, which will give the city a clearer picture of the rental landscape. Tenants who believe their unit falls short of the new standards will be able to lodge complaints with the city for free. And the city manager has been empowered to investigate claims, order fixes, and fine for noncompliance.

The power imbalance between landlords and tenants remains, but tenants say the regulations are a good start.

This feature was published one year ago today on the front page of the Laramie Boomerang. It is reprinted here by its author for posterity.

Laramie landlord kept $16K by allegedly double-charging rent, avoiding court

Brad Beck lived in Laramie for just three months. He would leave Wyoming’s sole university town with a bad taste in his mouth, feeling abused, threatened and mistreated by a prominent Laramie landlord.

In seeking justice, Beck said he came face to face with a legal system either powerless to help or uninterested in doing so.

“I’m both shocked and angry,” he said. “Shocked because Laramie is a wonderful town with wonderful people. I let my guard down because everybody was so kind and hardworking. Angry because Max is a rude egomaniac.”

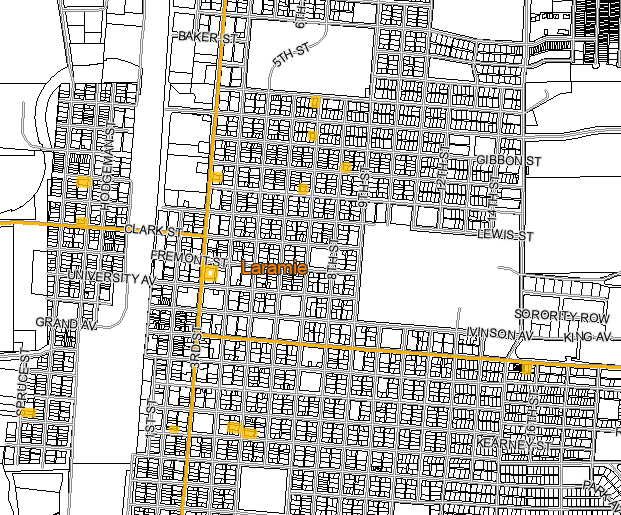

Maximus Bossarei is a local landlord and owner of what used to be the Xenion Motel in downtown Laramie. Although Beck didn’t know it at the time, his struggle mirrored that felt by more than a dozen other frustrated former tenants.

Bossarei is becoming notorious among some of Laramie’s renting population for the poor quality of his rental units, and his alleged practice of ripping off tenants and then dodging law enforcement.

The Laramie Boomerang examined a dozen civil suits filed in Albany County and spoke with several of Bossarei’s former tenants who allege a pattern of double renting, a practice of not returning deposits regardless of a unit’s condition, and a failure or unwillingness to maintain healthy living conditions for the people who inhabit his properties. The tenants point to Bossarei’s close relationship with Laramie City Councilor Jessica Stalder, who regularly acts as the go-between for Bossarei and his current or prospective tenants. Stalder also recently took on the role of executive director at Hospice of Laramie.

A number of these lawsuits were dismissed because Bossarei was not served with the summonses to appear in court.

Numerous efforts were made, including phone calls, emails and texts, to interview and solicit comment from Bossarei and Stalder. Neither responded to these requests.

‘Anything but honorable’

Beck, as many do, came to Laramie for a relatively short-term stay. As a structural concrete foreman for G.E. Johnson, Beck was assigned to a couple of campus projects, including the new Science Initiative Building.

For the duration of his assignment in Laramie — from October 2019 to January 2020 — he took up residence in Bossarei’s Xenion. While his lease officially lasted until May, Beck was reassigned to the Denver area and had to leave Laramie soon after the new year.

“I did not live there, but I did pay my rent for January, February, March and April, on time every month,” Beck said. “Always on time.”

Beck and his wife attempted to help sublease the place, even putting an ad on Craigslist.

“They used our unit as a model because we had it decorated and everything looked wonderful,” Beck said. “We had a lot of expensive furniture — which is probably the problem we’re having now.”

When Bossarei found someone new to take over the room, Beck was told that the furniture and other possessions he and his wife had not yet collected were moved into storage. That was when things began to get ugly.

“My wife and my daughter — who was a student at UW — went to pick up my things, and the only things he had stored were basically my clothing, my sheets, old food,” Beck said. “And my expensive furniture — the rugs, the paintings, and a $3,500 leather chair — were missing and he couldn’t account for them.”

Those items are still missing to this day.

Bossarei first excused the missing belongings by explaining the movers were “in quarantine in the hills,” and then became uncommunicative. So the Becks talked with the Laramie Police Department, hoping the police might help them locate their missing belongings. The Becks were told an officer would speak with Bossarei and later informed, by the police, that Bossarei said he would have their possessions returned soon.

What followed was a furious, and at times threatening, email exchange initiated by Bossarei.

The landlord boldly alleged that by talking to the police the Becks were opening themselves up to criminal and civil prosecution. He also asserted that the Becks actually owed him for a number of things — including May rent, despite that covering a period in which the Becks were living in Colorado and someone else was living in the Xenion unit.

“I hope you realize how your conduct has been anything but honorable and are willing to make this right before we are forced to escalate the matter further,” Bossarei writes in a May 18 email. “To be frank, given now the insult to injury caused here, we would spare no resources to do so if this is not handled properly by you.”

This kicked off a series of unproductive emails in which the Becks attempted to set up a day and time when they could collect the chair and other belongings, and in which Bossarei refused to cooperate until the Becks paid May rent or reassignment fees.

With the issue unresolved, the Becks eventually filed a civil suit with the Albany County Circuit Court, suing Bossarei for more than $4,000 in compensation for lost furniture and for unreturned deposits.

The court ordered Bossarei to appear on Dec. 20, 2020.

But this did not happen. Bossarei never appeared in court because the Albany County Sheriff’s Office never served the summons.

When a summons is not served in the state of Wyoming, the case is dismissed. The plaintiffs — in this case, the Becks — are allowed to bring the suit again, as long as they’re willing to pay an additional service fee. And Brad Beck said he plans on doing this.

Similar scenarios have played out with other tenants who have lived in Bossarei’s various properties across Laramie, and frequently, law enforcement fails to serve Bossarei the civil summons handed down by the Circuit Court.

To date, the total sum of contested amounts Bossarei has held onto — not by defending his case in court, but by failing to be served — is more than $16,000.

Double dipping, dodging law enforcement

Autumn Holmes shelled out $1,250 in rent and pet deposits in April 2020, paying Bossarei via the mobile payment app Venmo. Thus connected on the app — which lets you see friends’ transactions — Holmes could see when at least two other people put down deposits for the same unit, according to a civil suit filed in August.

Holmes saw these transactions just days after she communicated her intention to live elsewhere to Jessica Stalder, who was operating under her Facebook profile name “Jessica Rae,” according to the court document. Holmes requested the return of her deposit.

“I’m working on trying to re-rent the apartment first,” Stalder says via text in screenshots submitted with the civil suit. “No promises but hopefully when I do he can return the deposit.”

After this, according to the suit, Stalder stopped communicating with Holmes, and the deposit was never returned.

While other tenants spoke of Stalder’s involvement in their interactions with Bossarei, Holmes’ suit is the first time Stalder is explicitly named in court documents as Bossarei’s partner.

It is not, however, the first time Bossarei has been accused of double-dipping.

A thick stack of circuit court documents allege a pattern of keeping deposits from multiple prospective tenants, keeping deposits from tenants who left their units in good order, and charging multiple, successive tenants for the same apartment in instances where the first tenant moved out before the end of their lease.

To date, few tenants have successfully recovered those deposits, or double-charged rent payments — but not because Bossarei has made his case before the county’s circuit court.

From 2019-2020 — and once in 2017 — former Sheriff Dave O’Malley and his deputies repeatedly failed to serve Bossarei a notice to appear, although the court had commanded the sheriff to do so.

Sometimes, if a tenant has legal representation, a law firm will hire process servers to track down and serve an individual when the sheriff’s office has failed.

Charles Pelkey, a former representative in the state Legislature and local attorney, has represented a few people in disputes with Bossarei. That includes a case regarding an alleged double-charging of rent.

“What he’s doing is a violation of law that can be remedied in civil court — if we can get him served,” Pelkey said. “But he’s not servable because he’s the Artful Dodger. We have seriously good process servers — former cops and investigators. This guy just dodges.”

When a landlord fails to be served, tenants are left out in the cold without any recourse, and Bossarei is, by default, allowed to keep whatever sum of money was in controversy.

The Uniform Rules of the District Courts of the State of Wyoming make this possible.

“Cases on file for 90 days without service on the defendant will be dismissed by the court,” Rule 203b states. “Upon application to the court before the expiration of 90 days, and showing good cause, the time may be extended.”

Court documents show that in the last two years, Bossarei was able to keep more than $16,000 in contested, unreturned deposits, rent payments and other compensation simply by being unreachable by law enforcement.

“It’s court rules. It’s totally legal,” Pelkey said. “If we can’t get them served, they don’t know — they don’t officially know — that they’ve got a case pending against them.”

When a case is dismissed, it can be brought again, and several former tenants have tried repeatedly to get their day in court. But each time the case is brought again, those former tenants are charged $50 — a sum that goes to the sheriff’s office, whether deputies are successful in serving Bossarei or not.

That service fee can be prohibitive when former tenants are considering whether to sue, or whether to bring the case again, because many are poor.

According to a 2019 report from the Wyoming Community Development Authority, between 7,000 and 8,200 Albany County residents live in poverty. Depending on the specific measurement, that means 20-23% of the county population lives in poverty or extreme poverty. Statewide, that figure is less than 11%.

Those poverty statistics for the county are reflected in the high number of renters. According to the same report, more than 50% of the housing units in the county are renter-occupied. One third of the county’s renters have a “severe cost burden,” meaning they spend more than half of their income on housing. An even wider segment, 52%, have simply a “cost burden,” meaning they spend 30% or more of their income on housing.

Housing in Laramie has long been a topic of concern and conversation. While many landlords report amicable relationships with their tenants, the city’s tenant population knows that both the quality of housing and the treatment one receives from a rental unit’s owner can vary wildly.

The issue got significant attention during a February 2019 meeting of the Laramie City Council, during which the councilors discussed rental regulations, such as licensing requirements or periodic inspections.

A motion to consider (not necessarily implement) rental housing regulations was put to a vote and was narrowly defeated 5-4.

Freshman council member Jessica Stalder was one of the five councilors who killed the motion.

Double renting allegations

Laramie natives Zachariah LaBrake and his partner, Gabryelle, began leasing an apartment from Bossarei in July 2018.

What began as a miserable experience for the couple would eventually lead to a civil suit against Bossarei demanding nearly $5,000.

Like many of Bossarei’s tenants, they settled on something below their standards because it was one of the few places they could keep their cat and dog.

“We finally move in, and my first impression of that place is that it’s just a total shithole,” LaBrake said. “It was dirty and gross. There was a whole bunch of water damage. It was just a really bad place to live, and unhealthy.”

In December, he vacated the apartment even though he still had at least half a year left on his lease.

“Max explained to me that if they found a new tenant, he and his associate would terminate our lease when a new one began,” LaBrake writes in the small claims affidavit. “I continued to pay monthly rent from January 2019 to July 2019 in compliance with the lease.”

Shortly before the end of the lease term, LaBrake returned to the unit and let himself in using a spare key he still had. He discovered a fully furnished apartment and learned another person was living there. He notified Bossarei immediately.

“Someone else is living there in our place without our knowledge and permission,” LaBrake texted Bossarei. “Were you aware of this? How long has this been going on?”

Bossarei responded a few minutes later.

“Didn’t you guys move out a long time ago?” the landlord texted. “I’m not there much, so don’t know.”

As the conversation continued, LaBrake explained that they would like a refund for the months during which they paid rent while another person lived there. Bossarei asked if LaBrake and his partner had subleased the unit.

That question implies Bossarei did not know about anyone living in the unit, LaBrake said, so he began to wonder if he had, in fact, discovered a squatter in his old apartment.

LaBrake said he was growing concerned and texted Bossararei again.

“If you or no one else representing your company can explain to me who this person is, I may have to call the police and report that someone is living there illegally,” LaBrake texted Bossarei.

That was when the landlord became defensive.

“Why would you do that - you surrendered the premise, we had a final walkthrough and vacated it,” Bossarei texted. “Regardless, that is not going to solve anything anyways and will just complicate your situation … none of this would be an issue if you did not decide to move out early. We will sort it out once I can find out what happened and get back to you.”

So, LaBrake did not go to the police at that point, but he did begin speaking with the new, current tenant and learned she had been in the unit since March — meaning she had been there for nearly five full months at that point.

LaBrake alleges that Bossarei was collecting rent from both the previous and current tenant for that entire time, and talked to his mother’s lawyer. On the advice of that lawyer, he contacted the Laramie Police Department, hoping to open a fraud case against Bossarei.

LaBrake said an officer suggested he deal with the matter in civil court instead.

So LaBrake filed his complaint in small claims court, seeking $4,620 — the amount Bossarei collected from LaBrake while allegedly also collecting rent from the new tenant, plus LaBrake’s unreturned deposits.

The revelation that Bossarei had been allegedly double charging for the apartment was especially stinging for LaBrake because of an exchange he had with Bossarei the month before.

Misremembering that the lease had been for 13 months, rather than the standard 12, LaBrake wrote “Rent (final)” in the memo line of the check he sent to Bossarei. The landlord texted LaBrake to remind him that the lease still went for another month.

“During this time, he was also in contact with (the new tenant), who was living in that apartment and was knowingly taking rent from her, as well, and also speaking to her as her landlord,” LaBrake said. “So, he was fully aware that both of us were paying rent through that time and lied to us about it.”

The Albany County Sheriff’s Office was tasked with serving a summons to Bossarei, but was unsuccessful. LaBrake has so far dropped another $140 — $40 to file, $50 for each service attempt — in unsuccessful attempts to bring Bossarei to court.

“Defendant has been unable to be located or contacted,” reads a returned summons signed by Sheriff O’Malley. “Defendant will not return phone calls and does not live at address provided.”

LaBrake made a second attempt. The sheriff was sent out with another summons and was again unsuccessful.

“Seven service attempts were made at multiple addresses,” reads the second returned summons, also signed by O’Malley. “No other forwarding addresses available.”

Citing an inability to reach the defendant, Judge Robert Castor dismissed LaBrake’s case in January 2020.

LaBrake said he is considering a third attempt.

“It’s frustrating,” he said. “It’s disheartening, and it hurts my faith in our overall legal system that I don’t even have a chance to try to bring this man to justice.”

LaBrake said the amount in controversy — the $4,620 Bossarei allegedly cheated him out of — is about a quarter of his yearly income.

“That’s months and months of work that’s just all down the drain,” LaBrake said.

Paying rent all those months also meant it was impossible to pay rent at their new place, so Gabryelle’s father had to help them out, even as he paid his own rent for an apartment in Colorado.

If he is ever able to recover the money from Bossarei, LaBrake said he would like to pay back Gabryelle’s father for his help during that time.

“He didn’t hurt just me,” LaBrake said of Bossarei. “He hurt me, my family, my girlfriend, and my girlfriend’s father financially and emotionally.”

Keeping deposits

Alexandria Ekler has had a similar experience renting from Bossarei, although her dispute with the landlord is about an unreturned deposit.

She described her time renting from Bossarei and communicating with Stalder as an unpleasant one. For example, when the heat went out, Bossarei refused to fix it, Ekler said. When she got a space heater, Bossarei allegedly complained it was using too much electricity.

This alleged unwillingness to deal with maintenance issues is a complaint echoed by several former tenants — but it was not the source of Eckler’s main dispute with Bossarei.

Ekler’s lease ended in 2019, and she said she left the place cleaner than she found it.

“I freaking cleaned,” Eckler said. “I shampooed the carpet, I washed the walls, I cleaned the curtains that had cat hair from the previous renter on them. It was disgusting. But I cleaned everything, and it was spotless.”

It was disappointing, then, to Eckler when she did not receive any of the $1,445 she paid in security and pet deposits. Disappointing, but not surprising.

“I was ticked, and I was already ready for it,” Eckler said. “I already knew he wasn’t going to give it back. I had already heard the stories, so I already knew.”

Eckler considered seeking legal representation, but considered such a course of action too expensive.

“I wasn’t even sure I was ever going to get anything from him anyway, because people had sued him before and never came out with anything,” she said. “So, I just decided to do it myself.”

And Ekler is prepared to defend her claim in circuit court. Deeply suspicious of Bossarei given her experiences as his tenant, Eckler recorded the final walk-through, which was conducted by an unidentified associate of Bossarei’s.

But like so many other civil actions brought against Bossarei, the case never went to court because Bossarei was never served.

“Nobody can do anything about it because he won’t answer the door,” Eckler said. “You can’t make him, and therefore you can’t sue him. There’s nothing you can do.”

Not a single one of the former tenants interviewed for this story saw their deposit returned.

At least three other former tenants have tried to sue Bossarei for unreturned deposits, only to have their case dismissed when law enforcement deemed him unreachable.

Tracking down the ‘Artful Dodger’

The problem is not that Bossarei never makes public appearances. He showed up in person to speak against rental regulations in 2019. As the Laramie Human Rights Network has documented, Bossarei also called into a July 7 City Council meeting to voice his support for the police and praise Councilor Jessica Stalder without disclosing his relationship to her. He was also the master of ceremonies for a militia-recruiting event highlighted by WyoFile in the fall.

Beginning in February 2019, Sheriff O’Malley and his office did begin successfully serving Bossarei, occasionally summoning him to court.

Bossarei has been served successfully just three times: twice at the Xenion Motel, which he owns, and once at the Albany County Courthouse. Why he was at the courthouse is unclear, but Bossarei was served there the day after a state board ruled against him in a dispute with the county assessor.

Whenever Bossarei is successfully served, he countersues the tenants for a significant amount of money, to mixed results.

In March of 2019, Natividad Hernandez was seeking $1,850 for an unreturned deposit and alleged double-charged rent. Bossarei countersued Hernandez for more than $3,700, but eventually had to pay Hernandez $1,075 — the amount of the deposit.

In April of 2019, Valerie Burke and Adam Dewey were seeking $1,575 for unreturned security and pet deposits. Bossarei countersued them, this time for more than $4,700. They settled out of court, with the tenants paying Bossarei $725.

The only other time the sheriff’s office has successfully served Bossarei was in August 2020. Autumn Holmes is seeking $1,250 in damages for a deposit she paid and did not receive back. The case is ongoing, but Bossarei has filed a countersuit, demanding “no less than $4,000.”

These recent successful service attempts do not mean Bossarei is now always reachable. Brad Beck, for example, had his case thrown out just last month because of the failure to serve Bossarei.

The same happened for Gaelen Mackenzie, who filed his case in May 2019 and was represented by Charles Pelkey. Once again, it was a case involving alleged double-dipping.

When Mackenzie moved out of his rented residence a few months before the end of his lease, Bossarei re-rented the place to a new tenant.

“Defendant (Bossarei) continued to collect rent from Plaintiff (Mackenzie), despite a new renter moving into his Residence,” the complaint reads. “To date, Defendant has been collecting rent from both Plaintiff and the new renter, ever since the new renter moved into the Residence.”

Bossarei never offered a word in his own defense. He was simply never served.

The case was dismissed Aug. 19, 2019. Two days later, Pelkey and Mackenzie filed the complaint again, but once again, the sheriff’s office failed to serve Bossarei.

The case was dismissed a second time in December of that year.

Pelkey said he might try to bring the case again.

“I feel an obligation to the client more than anything else,” he said. “It’s a kid who got jacked out of several hundred, if not thousands, of dollars. And this guy’s just allegedly walking away with it like it’s just bonus money to him. It’s not right.”

Pelkey said he’s not the only lawyer in town to have this frustration. Unrelated to his work on the Mackenzie civil case, Pelkey also helped three young women get out of a lease they had signed with Bossarei.

Pelkey said in that case, the women had signed a lease for an apartment on Fifth Street, but hired an inspector to check the place out first. The inspector produced a report deeming the place uninhabitable, Pelkey said.

“Within a three-day window of signing the lease, they called (Bossarei) to cancel it,” Pelkey said. “He threatened to sue them for the entirety of the lease — which would be 12 months of rent, deposits, whatever else.”

When they came to Pelkey for assistance, the lawyer wrote a snarky letter to Bossarei, informing the landlord that he would now be representing the three would-be tenants and offered to share the inspection report.

“By the way, you’re an elusive fellow,” Pelkey writes in the letter. “I’ve been trying to serve you with papers in a lawsuit. I also know several other attorneys trying to serve you. Perhaps, we can all meet to discuss this and other pending matters. I sure think those other lawyers and I would appreciate the opportunity to speak with you in person.”

The proposed meeting never took place.

Unsettled out of court

Of course, those are only the unreturned deposits and rent payments contested in a court of law. Several former tenants interviewed for this story felt wronged by Bossarei, but also felt powerless to take him on given his legal track record — or rather, lack of one — as well as their own lived experiences as his tenants.

Jibran Ludwig and his partner were desperate to find a place when they moved to Laramie a little over a year ago. They wanted a two-bedroom apartment close to campus, one that allowed cats.

This was seemingly impossible in Laramie, Ludwig said, so after a summer of desperate searching, the pair settled on a small pet-friendly one-bedroom place just north of campus. It was one of Bossarei’s properties.

“We signed this lease — sight unseen, unfortunately,” he said. “We show up in early August to take a look at the apartment literally a few days before we move in. And it’s in pretty rough shape.”

The run-down apartment had mold problems, including a persistent smell, faulty appliances, and a damaged, leaky ceiling, Ludwig said. He and his partner attempted to resolve some of these issues by notifying Bossarei, but eventually gave up after it proved difficult to get help.

“The general pattern was one of deferred maintenance and deferred maintenance in ways that could potentially be more serious,” Ludwig said. “I think the thing that concerned me most about the apartment as someone living there was that persistent mildew/mold smell.”

Without protective equipment to deal with the mold on their own, and feeling as though they couldn’t expect help from Bossarei, Ludwig and his partner were at a loss.

“So we kind of just lived with this mold problem and hoped it wasn’t hurting us too much,” he said.

Ludwig described their interactions with their landlord as uncomfortable, to say the least.

“The understanding we had was, if there is a problem, either we had to fix it or we had to interact with Max, which was really unpleasant,” Ludwig said. “He was quite hostile about these things. It was not a pleasant thing to do, and it seemed unproductive. So at a certain point, we just kind of gave up contacting him about issues. It was just going to subject ourselves to this person who was very hostile in a lot of his interactions.”

Ludwig’s description of the state of the unit — and Bossarei’s unwillingness to help — were echoed by other former tenants, such as Trenton Zink.

Zink rented a unit on Fifth Street with his wife. It would be less than a year before the couple decided to move themselves and their baby out of that apartment.

Coming to Laramie — as many do — for school, Zink and his wife were glad to find a place, but it soon became clear that the unit was in poor condition. Zink said there were peeling tiles and electrical issues. In a recent modification to the apartment, Bossarei had ripped up the carpet and painted the hardwood brown.

“They didn’t put any seal on it, so it was just sticky brown paint that was constantly getting stuck if you went barefoot or had white socks,” Zink said.

Worse still, the garbage produced by that renovation was left in a pile around the side of the building. In addition to the carpet, the junk heap was also rife with nails, staples and at least one rusty saw blade.

“We could never let our child go outside, being around that stuff,” Zink said, adding that the rest of the yard was largely dirt or mud. “So we either went to the park or we stayed inside.”

With these problems — and the safety of their child — in mind, the couple searched for and found a new place to live, leaving a month before the end of their lease with Bossarei.

Bossarei allowed a friend of his to move into the vacated unit about three days after Zink’s family left, but continued to demand payment for the final month. Zink said a lawyer advised them not to pay that last month, and they didn’t.

Their deposit and pet deposit was never returned, but Zink decided not to press the matter in court. By then, he had heard several horror stories through the network of disillusioned former tenants left in Bossarei’s wake.

Zink and his wife were now caring for a second baby. COVID-19 had complicated everything, and they were still balancing work and school.

Ludwig and his partner also felt, before even making the attempt, that the legal system would fail them, as it has so many others.

Ludwig and his partner moved out more than two months ago, meaning their deposit — if it’s to be returned — is due to them. But based on conversations with other tenants of Bossarei and Ludwig’s own impressions throughout the lease term, the former tenant is sure that deposit will never materialize.

“We’re unlikely to contest this in court,” Ludwig said. “The experience we had as tenants was that Max would not hold up his end of the bargain, so there was very little reason for us to do the same.”

Ludwig said he and his partner did not leave the house in the best shape. Viewing the deposit as a sunk cost, the question became: why bother?

But the real reason they won’t be pursuing the deposit in court has more to do with Bossarei’s character and reputation than their odds in the court system.

“He’s really unpleasant to interact with — that’s just my takeaway,” Ludwig said. “I’m willing to give up $700 if it means never having to interact with him again.”

Speaking for a lot of renters here in Laramie, thank you Mr. Victor! I have heard so many stories from my friends about the horrible relationships they've had with landlords. Looking through your other stories it's easy to see which landlords are scared of being exposed as the trash they are. It's nice to have a journalist exposing the truth and helping the little guy (the renters, just so we're clear. Landlords are in no way the victims here) Thank you for shedding light on the otherwise unheard voices. You have seriously helped Laramie change for the better!