Police standards commission cannot view personnel records, but lawmakers seek fix

POST certifies and decertifies law enforcement officers, but it can’t access psych evals or disciplinary records. State legislators will consider a bill this November aimed at fixing the problem.

Five years ago this November, an Albany County Sheriff’s deputy with a noted history of violence initiated a traffic stop with Debbie Hinkel’s son, Robbie Ramirez. The encounter escalated quickly and ended with the deputy shooting Ramirez three times, including twice in the back, landing shots in the man’s liver and spine.

The shooting and its fallout sparked a local campaign for greater police accountability, transparency and oversight.

The deputy is no longer working for the Albany County Sheriff’s Office, but he was never officially decertified by the state commission responsible for penalizing badly behaved cops.

Hinkel told the Wyoming Legislature’s Joint Judiciary Committee Tuesday that she struggles with this fact.

“We had over 2,000 signatures of people feeling like he should be decertified,” she said. “The overall attitude in Laramie was an attitude of fear and anxiety with all police officers — not just the sheriff's department, not just the officer involved, but with all police officers. It was a serious problem. It's taken a long time, and I have to tell you I woke up every morning, for four and a half years, not thinking about my son being killed but the total lack of justice.”

Part of the issue, Hinkel said, was that Colling had the protection of what others have called the “good ole boys” club, which allegedly shielded him from discipline. But there’s another problem, one that lawmakers could and might fix:

The agency responsible for certifying and decertifying peace officers cannot access an officer’s personnel records without that officer’s permission.

But the Joint Judiciary Committee could bring legislation in 2024 that would make it easier for these authorities to investigate complaints about officers like Colling. The committee discussed the potential for this legislation when it met earlier this week.

When the committee meets again later this fall — just two days after the anniversary of Ramirez’s death — its members will decide whether to endorse that legislation.

POST and its problem

The Peace Officer Standards and Training Commission — known colloquially as POST — is responsible for determining if individuals are fit to be peace officers in Wyoming. That means both certifying new recruits and decertifying current or recent officers who, for example, commit felonies or through their actions hurt public trust in law enforcement.

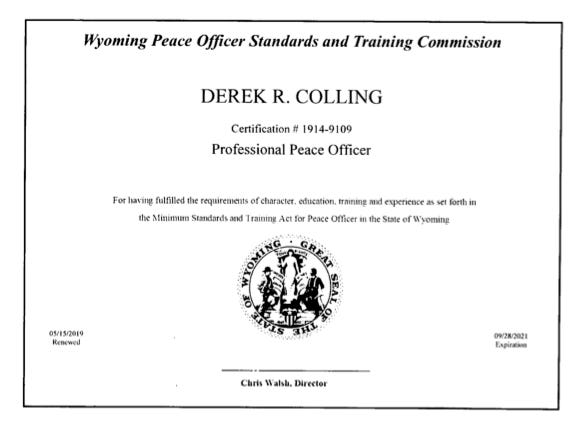

POST has spent at least three years mulling the decertification of Derek Colling, the man who killed Hinkel’s son under the color of law.

But POST Director Chris Walsh has found that he’s not allowed to access the personnel records — including psychological evaluations and disciplinary reports — that would help him make a determination. Despite his legal responsibility to hold Wyoming peace officers accountable, state law doesn’t explicitly let him access the records he says he needs — and the courts have been unwilling to interpret the vaguely written laws in his favor.

“On one hand, I'm supposed to validate to the state of Wyoming and all the citizens of Wyoming that these people meet the requirements,” Walsh said. “In reality, I cannot do that if people don't want to be forthcoming.”

The discrepancy between Walsh’s responsibilities and the letter of the law came to a head in Albany County District Court last month, as Walsh sought the release of Colling’s personnel records. The Albany County Sheriff’s Office, Albany County Attorney’s Office and Colling himself fought the release of those records and were ultimately successful in keeping those documents out of Walsh’s hands.

District Court Judge Misha Westby said without clear statutory guidance dictating the release, law enforcement agencies and the peace officers who used to work for them are not officially required to hand over potentially sensitive material.

“It also seems to me there should be an exception [for POST to access these records],” Westby said. “But I can’t find an exception that applies.”

A police officer’s privacy, a state commission’s responsibility, and the people’s right to know

It all comes down to the letter of the law.

The Wyoming Public Records Act was passed in 1969 and ordered “that all of the state’s public records shall be open for inspection by any person at reasonable times,” with some notable exceptions. That’s according to a Legislative Service Office memo prepared at the behest of Laramie Representative Karlee Provenza (HD-45).

Exceptions to the public records act fall into two categories

Discretionary. (These exceptions are up to the government official responsible for the relevant records. This happens when the official decides that the release of the requested records would be “contrary to public interest” for one reason or another.)

Mandatory. (The government official responsible for the requested records “shall deny” requests for some specific government materials, regardless of their feelings about the public interest.)

The details are complicated. Some guidance is provided by the public records act itself. The Wyoming Supreme Court has also decided some edge cases where the line between public record and protected information wasn’t yet clear. (So, for example, you are allowed to request the salaries of school district employees thanks to a 2011 ruling.)

Personnel records — such as a peace officer’s psychological evaluations — usually fall under the category of “mandatory” exception. If you request them, your request will be denied.

But there are exceptions to the exception. A random member of the public might not need to access a government employee’s personnel records, but that employee’s supervisor certainly does.

So the Wyoming Public Records Act also specifies that personnel records “shall be available to the duly elected and appointed officials who supervise the work of the person in interest.”

The question of the hour is this: Does the director of POST count as an “appointed official” who supervises the work of a peace officer?

Under current state statute, not necessarily.

Courts and law enforcement agencies have often played it safe, denying Walsh personnel records when he’s come looking for them.

“I've had this position since 2019,” Walsh told the judiciary committee. “And since 2019, I've had occasion to request [six] records through subpoena. Two of those were on the same case. Three of those subpoenas were not honored.”

Walsh said law enforcement agencies are afraid of being sued by whatever former officer is under investigation. Allen Thompson, the director of the Wyoming Association of Sheriffs and Chiefs of Police, said it’s something law enforcement leaders in Wyoming are discussing.

“The general information that I'm receiving from our membership is they're interested in providing these records to POST as long as it doesn't open them to any kind of liability or violation of other statutes,” Thompson said.

So Walsh asked lawmakers to clarify, unambiguously and in state law, that his agency has a right to access those personnel records.

Making a second attempt

Rep. Provenza tried to eliminate the law’s ambiguity during the last legislative session, sponsoring a bill that would have explicitly required “personnel files of peace and corrections officers and dispatchers to be available to the peace officer standards and training commission.”

The bill, HB173, was sponsored not just by Provenza, but also by Rep. Art Washut (HD-36) and Sen. Cale Case (SD-25) — all of them members of the judiciary committee.

The bill won committee endorsement, but died among a mountain of other bills when they failed to be considered by the full House before a key deadline. (This mountain of dead bills also included committee-backed efforts to expand Medicaid and to pass a state shield law for journalists.)

During its meeting this week, the committee asked the Legislative Service Office to again craft a bill allowing the release of personnel records to POST. The new bill will largely resemble last year’s HB173.

The committee is scheduled to meet Nov. 6-7 in Douglas.