The Laramie Reporter’s 2023 Essays

Reflecting on the stories and editorials that abandoned the “inverted pyramid.” Each essay grappled with big picture themes typically falling outside the purview of journalism.

One benefit of running your own news outlet is that you get to call the shots — on newsworthiness, on style, on presentation, on just about everything.

It’s scary as hell. But it’s also liberating.

In 2021, I was basically the only reporter who believed a deep-dive investigation into one particular slumlord was worthy of print. I took my inspiration from places like the Behind the Bastards podcast, which focuses on malevolent individuals as a way to explore larger issues and trends. That style of reporting wasn’t and still isn’t very popular in mainstream Wyoming outlets, but I knew it was the right call for that story.

Taking an unorthodox approach allowed me to explore angles that would have gone unnoticed if the piece had a more general focus.

Since then, I’ve leaned into this freedom in my work for the Laramie Reporter. And that was never more true than this year — the year I explored kidney donation and humanism, the long legacy of an infamous hate crime, and the rhetoric of bigotry. These topics, I believe, are worthy of journalistic or at least editorial attention. But they’re not the sort of stories one would find in a typical local newspaper or zine.

While I love newswriting — and you can expect continuing coverage, investigation and analysis of Laramie happenings in 2024 — the essays below are some of what I’m proudest of from the past year.

It’s not easy running one’s own news outlet, but I now have the freedom to explore themes and ideas relevant to local readers yet absent from other platforms.

The list below is a celebration of that fact … and a naked attempt to direct your attention to some of our top stories from 2023 as we, behind the scenes, embark on bigger and bolder stories in 2024.

Kidney.

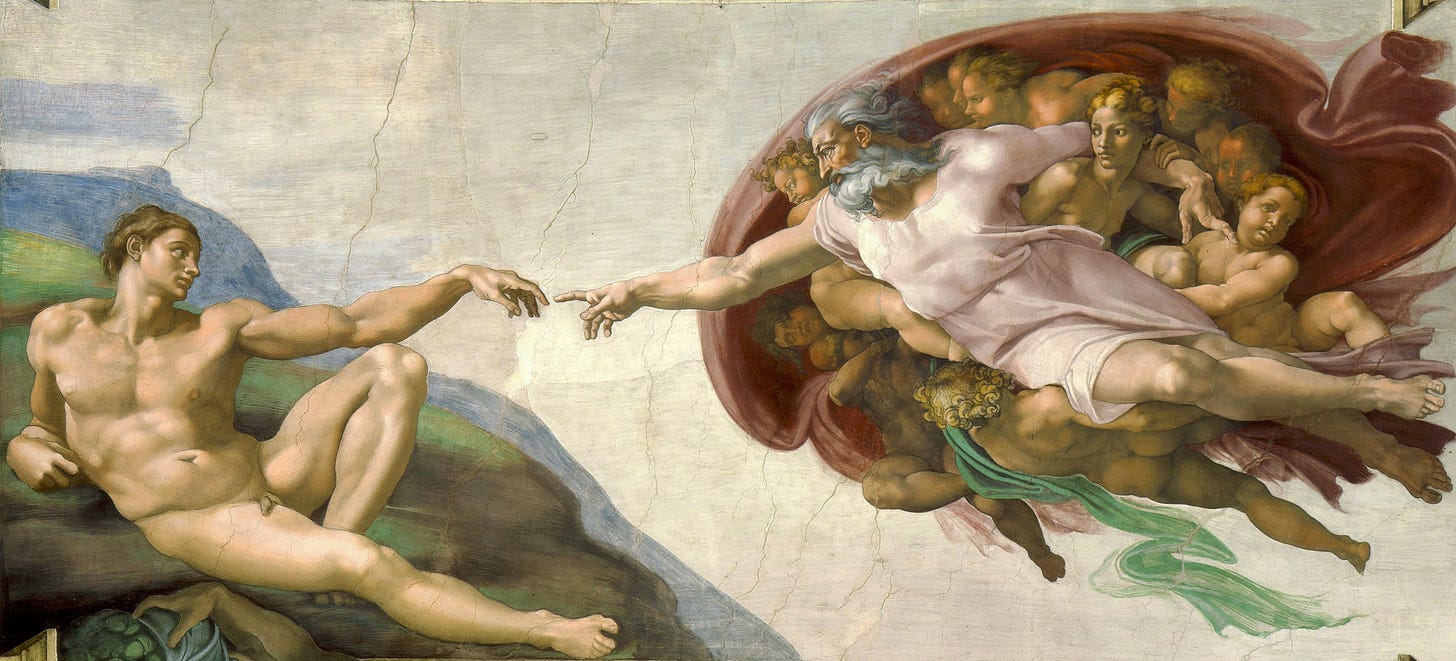

It’s surprising to some that I am a kidney donor because I have been vocal about my atheism.

I am not a “lapsed Catholic” nor am I a fan of hiding my atheism behind an “agnostic” modifier. I don’t believe in gods, or afterlives, or souls and I don’t believe life has any inherent meaning. I don’t go to church or pray or follow any commandments. I don’t believe in Jesus Christ and I wouldn’t worship him if I did.

So if that’s the state of my philosophical and ethical outlook, why would I share my spare?

Well, ‘irreligious’ does not mean ‘immoral.’ It’s true that I don’t have a holy book to cherry-pick, but I live in a human community with a rich tradition of debating, deciding and advancing new moral precepts. I can recognize the flourishing or suffering of other creatures and work to encourage the first while eliminating the latter. And aside from all of that, it just feels good helping people. I think Christians feel that too. Sure, your god tells you to feed the hungry, but if he didn’t, wouldn’t you still feed the hungry? I think you would. I think you would still be good even if no one was telling you to be.

I wrote this essay to get at that point. The most unambiguously good thing I have ever done — donating a kidney and sparing someone from years of grueling dialysis treatments — did not happen in spite of my atheism. In many ways, I donated because of it.

Atheism is simply one answer to one question. What’s actually interesting is what you do next. So, basically, you’ve realized there’s no god. What does that mean? What does that really mean?

For me — and for many of my ilk — it means we’re alone. There is no god coming to save us. Maybe that’s sad. Maybe that’s scary. But mostly it should fill us with a vigor and purpose to care for each other. We are all we have.

Thankfully, we’re enough.

“There’s no praying our way out of this,” I wrote last August. “There’s no miracle or divine intervention that will get these kidneys pumping again. If there’s going to be a solution, it has to come from us. So we ask what can be done. And the answer … is clear. We cut ourselves open and give until it hurts.”

What do we owe Matthew Shepard?

Matthew's death 25 years ago was a stark reminder of the hatred poisoning America.

This story, like the one below, began as a more traditional journalistic endeavor. It had been a quarter century since the hate crime that claimed Shepard’s life. It felt appropriate to recognize the anniversary in a big way.

The infamous crime was actually a huge blind spot in my knowledge of Laramie’s history. I was more intimately familiar with the event’s ripples than the event itself. So writing a standard “looking back” 25th anniversary story also felt like an opportunity to round out my knowledge.

But one interview led to another until I was fully immersed in the Laramie of 1998. Old-timers told me how the heinous events caused them to examine their own innate biases. Matthew’s friends told me, smiling, how fiercely they resisted the forces of hatred and bigotry in the wake of the crime. Matthew’s mother told me she was disappointed with Wyoming yet somehow, amazingly, eternally hopeful for the future.

Together, they painted a picture of a violent human tragedy replete with stark visuals — of angels spreading their wings, of parents sparing the murderer of their child. In one interview after another, I got a clearer and clearer sense of the event’s contemporary implications and its historical echoes.

It got me asking questions about Laramie’s culpability and about the future of my state and country. On that latter point, I come down more pessimistic than any of my sources.

Wyoming still does not have a nondiscrimination statute. Nor is it likely to get one. As far-right challengers drive the state’s Republican party closer and closer to its most extreme edges, it seems far more likely that anti-LGBTQ legislation will become the norm, a perennial backlash to a wider world that has grown more accepting and tolerant and loving.

And the so-called Equality State will play host to that clash of cultures — its young people fleeing for more diverse pastures, its remainers railing against even the most modest proposals of people like Judy Shepard.

“The attacks on our transgender brothers and sisters are not a tragedy of the past,” I wrote in October. “They are a tragedy in the making. As Laramie faced a reckoning in 1998, we face a question today: How do we avoid further tragedy?”

Riley Gaines vs. the world

This story also started with a traditional news pitch: Let’s fact-check the national speaker coming to campus. Riley Gaines is allegedly interested in a singular goal: Banning trans women and girls from female sports.

So surely, we thought before the speech, she’ll make concrete claims about the state of women’s sports, or about transgender inclusion in society, and we can do the work to verify or falsify those claims. The end result, we figured, would be of use to anyone interested in the topic. And this topic in particular was recently debated at the highest levels of state government — so it’s likely on many readers’ minds, whether or not they’re interested in what Gaines is selling.

The morning after Gaines’ speech, I went over my notes and started pulling out and listing factual assertions she had made. It became clear this would be no easy task.

More than facts, Gaines spoke in terms of emotions and tropes. If she had said trans women are dominating every sport, or even just swimming, that would be easy to check. (They’re not, by the way. Gaines lost her most famous event to four cis women, and the trans woman who tied with her would have lost all of her events to cis women if she competed in earlier years.) Instead, Gaines leaned more on her feelings about trans women — that they are scary or threatening or gross — than actual facts. Her speech was about how she felt unsafe around trans women, not about any actual, verifiable violence. Her speech was also about how she felt disadvantaged competing against them, not about any facts or figures regarding performance.

Now, I don’t like to attribute intentions to the people I’m publicly critical of. Yes, some of them certainly act like liars. But it’s always possible they’re just idiots. Or have fallen deep into motivated reasoning.

But one way or the other, Riley Gaines doesn’t really know what she’s talking about.

If she were to cite stats on violence, for example, she would have to admit that trans women are in way more danger than the cis women around them. If she cited stats on trans performance in female sports, she would have to admit there’s no epidemic of men pretending to be women to win collegiate sports championships.

Gaines lives in a world of anecdotes and unexamined impulses. But we don’t have to.

There were plenty of weird elements in her speech — from the cruel comments to the casual anti-trans hatred to the (literal) fascist talking points — that I could pull it apart and hopefully help answer the question: What is going on here?

I had a lot of fun digging into the topics and tropes raised by Gaines and getting a sense for the actual conversations adults are having about the tension between inclusivity and fair competition.

There’s actually a fascinating discourse happening at the intersection of science, sports and human rights among people who are committed to all three. But Gaines is only half-interested in one of those — and has no interest in earnest discussion — so her thoughts on the matter are undercooked, shameful and useless.

“Those who find themselves on stage or at the helm of a local news outlet have moral responsibilities above and beyond those with lesser platforms,” I wrote in November. “That exalted position demands more careful consideration of what we say and what we don’t and how nefarious factions might use what we say to achieve monstrous ends.”

Kate Cohen's "We of Little Faith" is a great take on being out as an atheist.

Then there's the story:

The Rabbi was asked by one of his students “Why did God create atheists?”

After a long pause, the rabbi responded. "God created atheists to teach us the most important lesson of them all – the lesson of true compassion. You see, when an atheist performs an act of charity, visits someone who is sick, helps someone in need, and cares for the world, he is not doing so because of some religious teaching. He does not believe that God commanded him to perform this act. In fact, he does not believe in God at all, so his actions are based on his sense of morality. Look at the kindness he bestows on others simply because he feels it to be right.

"When someone reaches out to you for help. You should never say ’ll pray that God will help you.' Instead, for that moment, you should become an atheist – imagine there is no God who could help, and say 'I will help you.'”

Thanks for all your good work, Jeff, and your commitment to the Laramie community.